A smattering of rain and snow in early October gives us hope that 2022 will be a wet year and our two year drought will come to an end. Maybe it will, and maybe it won’t.

2020 was dry. 2021 was one of the very driest years we’ve seen over the last century.

Moreover, groundwater levels have continuously declined, so it is increasingly difficult to rely on our aquifers when precipitation is scarce. Wells have gone dry across the state. Many small Central Valley communities rely solely on groundwater (and the quality can be unfit to drink even when it is available). Cities on the Mendocino Coast have resorted to bringing in water by truck water for the past month, as wells have gone dry.

Conditions in California’s larger urban centers vary. Marin County is considering building a permanent pipeline across the Richmond – San Rafael Bridge (Marin built such a pipeline in 1977 but removed it a few years later). Zone 7, which relies on the State Water Project supplies and limited local groundwater to serve Pleasanton and Livermore, is requiring customers to cut back. And Valley Water, the Bay Area’s largest supplier serving the South Bay, has told its customers that Santa Clara County is “in an extreme and exceptional drought.”

For the most part, urban southern California is faring better. The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and its customers have built local surface storage, invested heavily in recycling and has stored groundwater locally, in the Central Valley and in the Mojave Desert. The East Bay Municipal Utility District will be accessing additional supplies from the Sacramento River through its diversion facility at Freeport – a project completed just a decade ago.

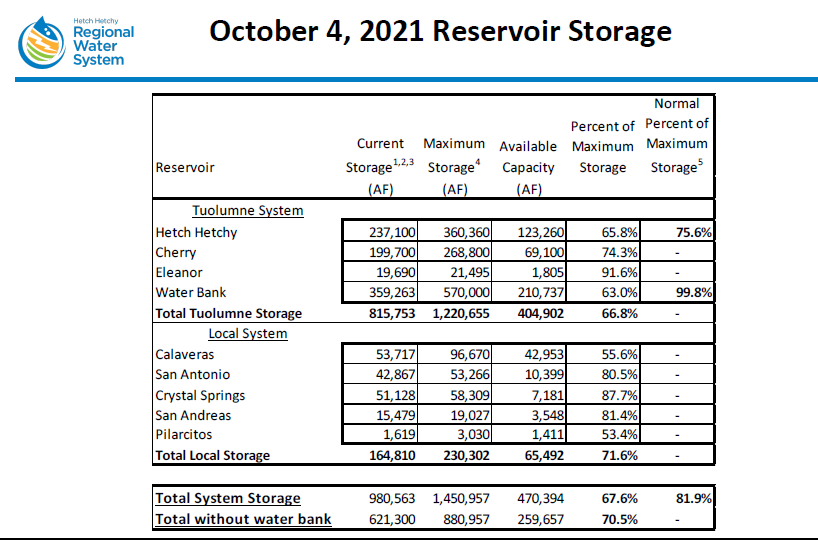

San Francisco’s Regional Water System is also in pretty decent shape. The SFPUC reports it has 980,563 acre-feet in its nine reservoirs – roughly enough to supply its customers for four years even if its does not rain a drop. See Figure 1.

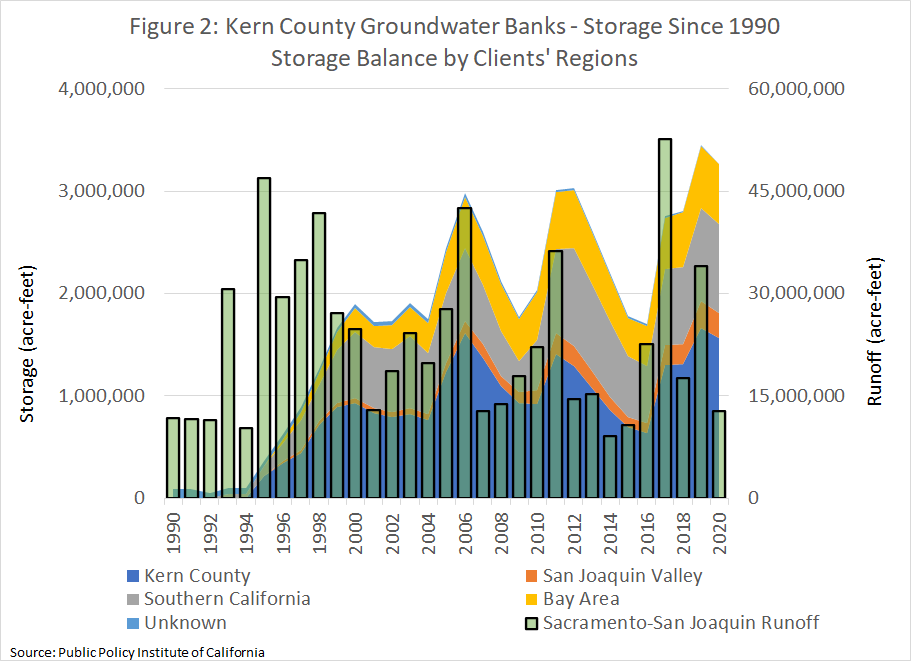

Restoring Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park will not mean any reduction in water supply or any loss of reliability. For example, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission could invest in groundwater recharge to replace the storage function of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, as so many of California’s cities have done over the last 30 years (see Figure 2). The battle to convince leaders in San Francisco is partly economic, but mostly political. Not a drop of water need be lost!

Since modest investment in the early 1990’s Kern County’s groundwater banks have provided substantial benefits for farmers and cities alike. Figure 2 shows the aquifers are recharged in years when river runoff is high, and those supplies are then withdrawn in drier years.