2022 marks a third consecutive dry year in California. Urban water agencies in both southern California and the East Bay are mandating limits for their customers. And Central Valley farmers are making difficult decisions about what crops to grow and what fields to fallow.

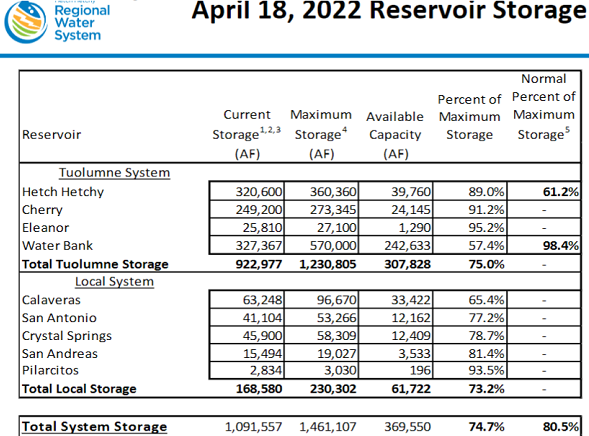

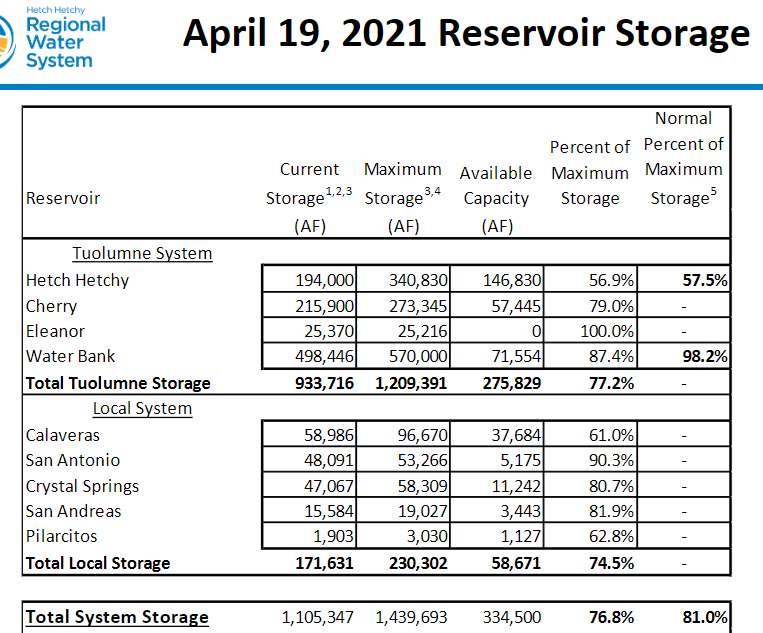

San Francisco, however, has relatively plentiful supplies in storage. Their nine surface reservoirs contain almost the identical amount of water that they did a year ago – more than a million acre-feet and roughly 5 years of supply. (San Francisco also operates two smallish groundwater banks.)

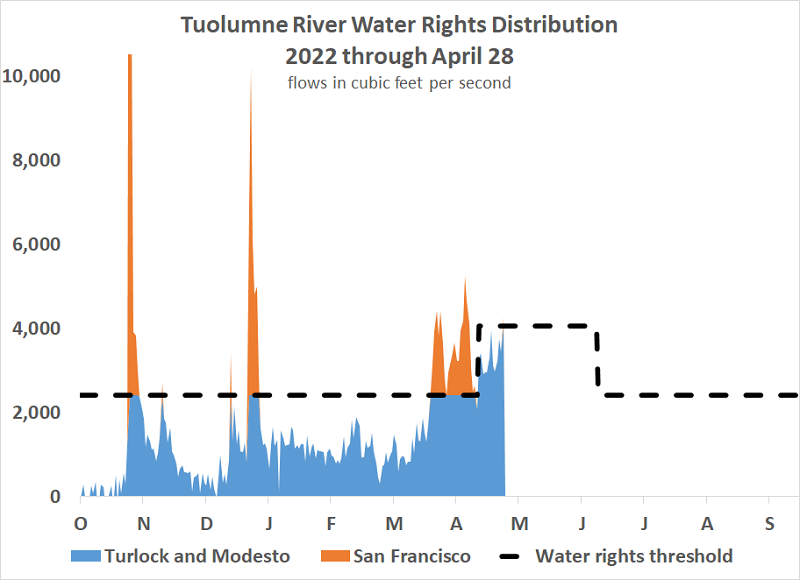

In some dry years, San Francisco’s junior water rights on the Tuolumne River yield almost no supply – the Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts get it all. 2022 was different. San Francisco received substantial amounts during the two early season storms that caused high flows on the Tuolumne River for short durations. Had that same amount of water flowed at lower rates for a longer period, none of it would have belonged to San Francisco.

(Water rights on the Tuolumne work like this: Natural flow is measured/calculated on a daily basis in cubic feet per second. For most of the year, the Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts get the first 2416 CFS, and San Francisco gets only those flows above that threshold. During the peak snowmelt season from mid-April through mid-June, that threshold increases to 4066 CFS. See below.)

Water rights on the Tuolumne and elsewhere in California can be described as inane and cattywampus.

While water agencies, including San Francisco, do need to operate conservatively to meet the needs of their customers, some argue that San Francisco hoards too much water in dry years.

Whatever level of reliability is warranted, Restore Hetch Hetchy urges San Francisco to invest in system improvements that will replace the storage function of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and allow Hetch Hetchy Valley to be restored.