Imagine the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, between Fresno and Bakersfield but along the west side of the Central Valley. At 690 square miles, Tulare Lake was 3 1/2 times the size of Lake Tahoe. Many believe the largest population of native people in what is now the United States lived along the Tulare lake, supported by its plants, fisheries and wildlife.

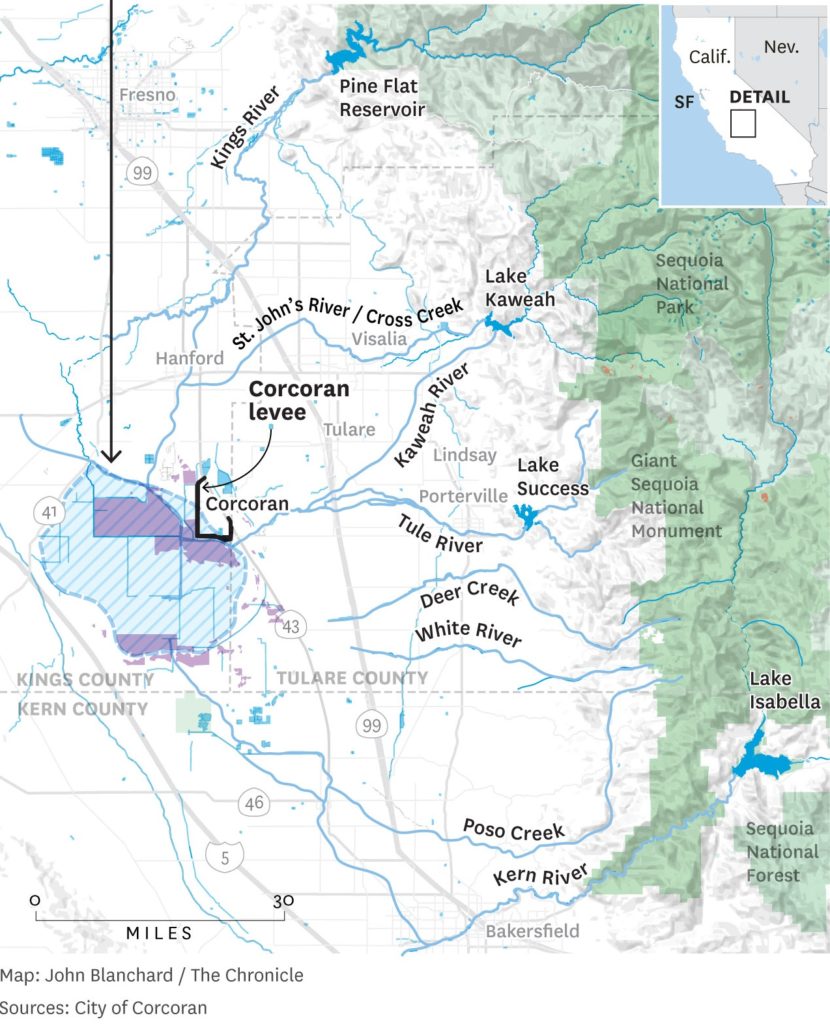

The Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern are the principal Tulare Basin rivers that drain the southern Sierra, historically flowing into terminal lakes. Principal central Sierra rivers such as the San Joaquin, Merced, Tuolumne and Stanislaus flow north toward the Delta, albeit after being mostly diverted for agriculture or direct human consumption. Currently flooded areas are shown in purple.

Beginning around 1870, Americans began to control the waters feeding Tulare lake and to irrigate the productive land, pushing native peoples out. Today, the former lake bed is mostly farms and ranches, but also includes some small towns.

In most years, the rivers feeding Tulare Lake are fully controlled upstream. For the first time in 26 years, however, heavy March rains reached Tulare Lake, breaking levees and flooding farms and homes. People are even more worried, however, about what will happen when the record southern Sierra snowpack melts. (The town of Corcoran, for example, with a population of 22,0000 is taking emergency action to raise its levees.)

Renowned journalist Lois Henry reports that the J.G. Boswell Company has broken levees to flood other farmers and protect is own land, raising additional questions and no small amount of suspicion in advance of the impending snowmelt. (Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America, John M Barry, is a fascinating book which tells a story of breaking levees to divert floodwaters, helping to elect Huey Long as Governor then Senator, Herbert Hoover as President as well as reinvigorate Ku Klux Klan.)

There is concern further north as well. The “capacity” of the Tuolumne River through Modesto, is only about 11,000 cubic feet per second. There is still space in Don Pedro, Cherry and Hetch Hetchy Reservoirs, to absorb some of the spring snowmelt, but a sudden prolonged hot spell, or worse yet a substantial warm rain, could cause flooding along the Tuolumne. (Hetch Hetchy Reservoir does not need to leave space for flood control as that “space” was transferred to New Don Pedro in 1970.)

California is a semi-arid state (well, maybe not this year), always facing challenges to support its population, agricultural sector and natural environment. For most of us, 2023 is a welcome relief and it feels good to be wet again. But the winter’s storms have come at a cost which we will not fully understand until the snow melts.