2021 is the 4th driest year since 1906, and last year was dry as well. Two dry years make a drought these days, especially since our aquifers are more depleted than ever. Here’s hoping 2022 will be a gully washer and may it come soon.

In droughts, California’s historically based system of allocating water “rights” comes into play. While everyone may suffer, the pain is not equally shared. Examples below include the federal Central Valley Project’s San Joaquin Valley customers, water users on the Stanislaus River and water users on the Tuolumne River (which includes, of course, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission and its Hetch Hetchy Reservoir).

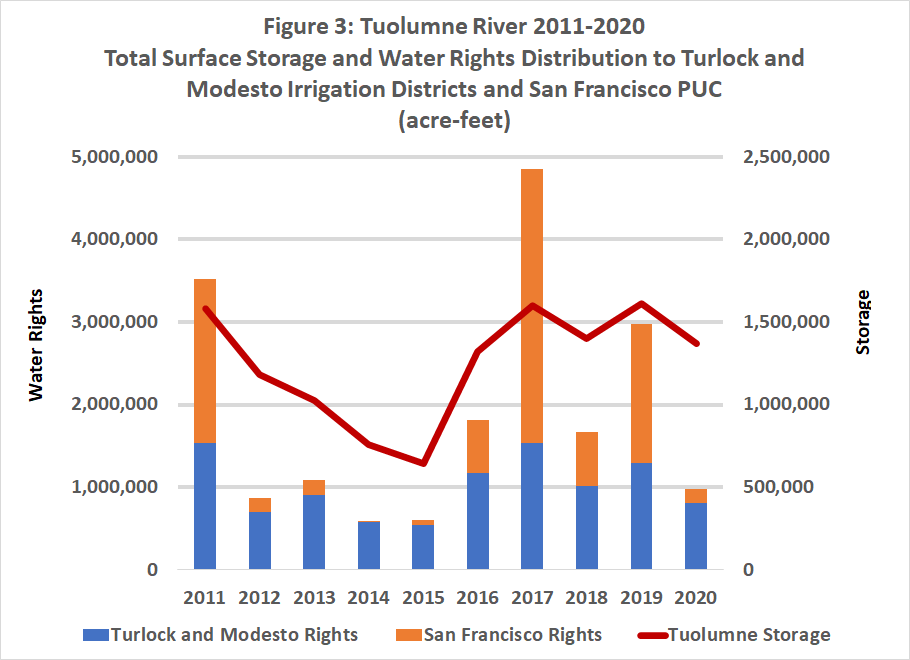

Figure 1 below shows storage levels in Shasta Reservoir, the largest in California, and selected Central Valley Project deliveries to the San Joaquin Valley, including (1) Exchange Contractors, (2) Wildlife Refuges and (3) Westlands Water District for the ten-year period from 2011-2020. The Exchange Contractors are farmers who originally had senior rights on the San Joaquin River but “exchanged” them for water delivered from northern California and through the Delta. The Central Valley Project Improvement Act, passed in 1992, includes provisions to deliver water to managed wetlands in the San Joaquin Valley to mitigate, in part, for the wetlands that were dried up to make room and provide water for agriculture. Both the Exchange Contractors and Wildlife Refuges have priority that is senior to the “Water Service” contractors, whose water supply is available only when the needs of senior rights holders have been met.

Westlands Water District is the largest of the Water Service Contractors. Much of the land is very productive, but Westlands has junior water rights and has historically relied on litigation to get every drop of water possible. Farmers in Westlands often grow a mix of lower value annual “row” crops (e.g. tomatoes) and higher value orchard crops (almonds etc.). They will often fallow the annual crops in dry years and use what water they are allocated or can buy for their orchards. Many have been very successful with this strategy but some have also gone bankrupt.

As Figure 1 shows, deliveries to the Exchange Contractors and Wildlife Refuges are mostly consistent, but deliveries to Westlands plummet in dry years.

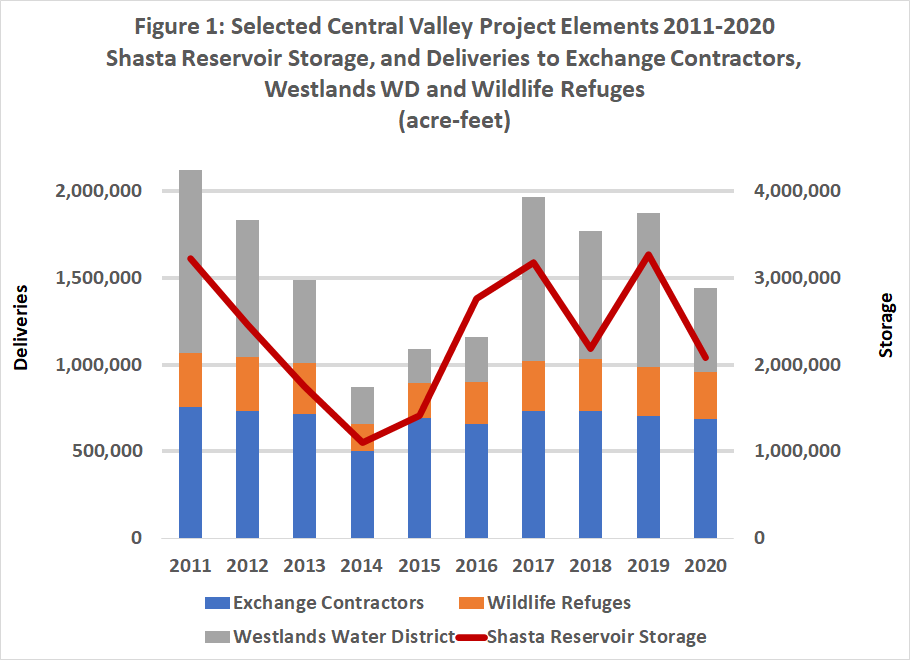

Figure 2 shows New Melones Reservoir and operations on the Stanislaus River. Completed circa 1980, New Melones Reservoir was the last major on-stream reservoir constructed in California. It is also part of the Central Valley Project, but it is operated for the benefit of farms near the Stanislaus River. Part of the agreement prior to the construction of New Melones Reservoir included assurances the rights of the Oakdale and South San Joaquin Irrigation Districts would be met before deliveries to others would be made. (Releases from New Melones are also used to meet dilute salt loads in the south Delta.) When there is extra water available, modest deliveries to the Stockton East Water District are made. Figure 2 also shows that New Melones was nearly empty in 2015.

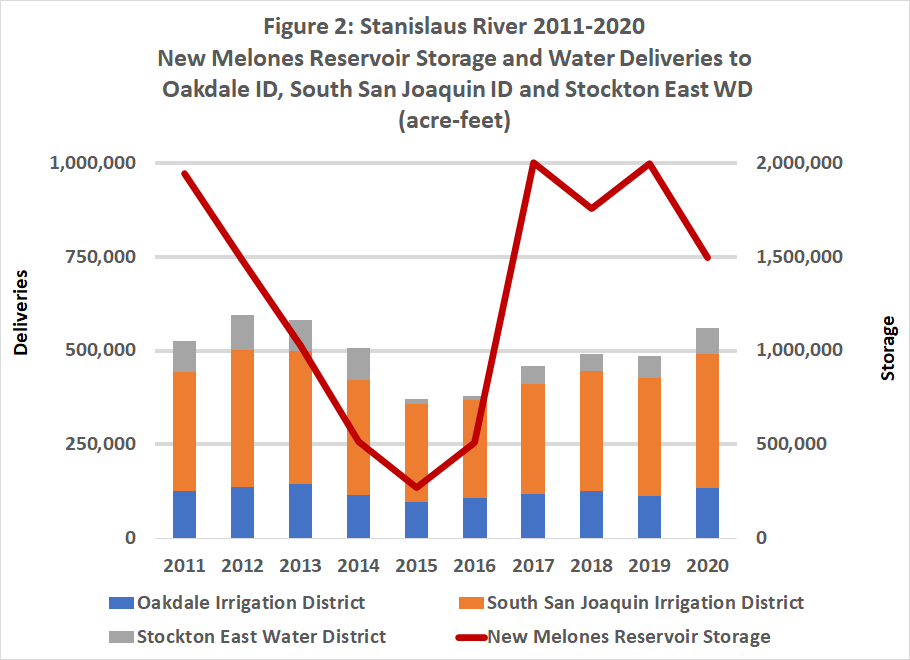

Figure 3 provides a synopsis of water storage and the distribution of water rights on the Tuolumne River from 2011 until 2020. Don Pedro is the largest reservoir on the Tuolumne, but Hetch Hetchy, Cherry and Eleanor Reservoirs provide additional storage capacity. The Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts use about 4 times as much of the river’s water as does the San Francisco PUC, but roughly one-half of all the surface storage belongs to San Francisco. San Francisco relies on this storage to meet its needs in dry years when its water rights are minimal (see 2012-2015 and 2020 below).

As a result of its extraordinary investment in storage, the San Francisco PUC has a very reliable system (but like all water agencies, they rightfully worry about extended droughts). As a result of San Francisco’s practices, storage in Tuolumne River reservoirs is generally kept at relatively high levels.

Restore Hetch Hetchy is keenly ware of San Francisco’s rights, demands and other facilities as we pursue and advocate for groundwater banking, recycling and other alternatives will replace the water supply function of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir.