In a “Dog Bites Man” story, California farmers have proposed emptying Lake Powell, the reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam, which would allow Glen Canyon to be restored.

Colorado River flows seem unlikely ever to fill Lakes Powell and Mead, and farmers say evaporative losses at Powell outweigh any storage benefits.

The Imperial Valley farmers did not suddenly become afficionados of desert canyons. They are still interested in maximizing their water supply so they can grow as much food as possible. Their interest comes in the wake of diminishing water supplies on the Colorado River over past decades and the threat of cuts to their share of those supplies.

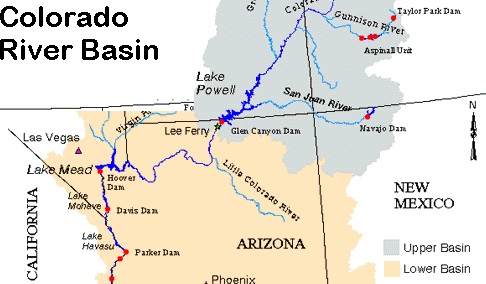

Evaporation is a factor in all reservoir systems and is largely dependent on the surface area of the reservoirs and the ambient temperature. Seepage is also dependent on size as well as the geology of the land below. Lake Powell is estimated to lose 860,000 of water acre-feet per year. Lake Mead loses a similar amount. Since neither reservoir seems likely to fill anytime soon, the idea of eliminating one of the reservoirs to cut down on losses makes intuitive sense.

The farmers’ math replicates what environmentalists have been saying for decades – that the loss of water due to evaporation and seepage at Glen Canyon make the Colorado River’s water storage system less reliable – i.e. the dam loses water.

Analyzing this fundamental question is not a simple matter, in part because whether Glen Canyon Dam improves or diminishes water supply reliability depends on future flow patterns. Perhaps not surprisingly, risk averse government engineers have not addressed this question to date. It would be nice if they had responded to those pesky environmentalists, but the Imperial Valley farmers will be harder to ignore.

There are other issues at play, besides water supply and restoring Glen Canyon. The city of Page, Arizona, (population 7,247) draws water directly from Lake Powell – what will its fate be if the lake is emptied? How would overall hydropower generation be affected if more water were stored in Lake Mead and none in Lake Powell – and how might the upstream communities who lose hydropower be compensated?

Let’s crunch the numbers to compare water supply, hydropower and environmental benefits while addressing how communities can work together at Glen Canyon. Let’s do it at Hetch Hetchy as well. We don’t need to live with mistakes of the past.

One of Glen Canyon’s many side canyons.