The thrill of whitewater: A dory and its passengers run the Grand Canyon’s Crystal Rapid in 1983, a high water year when unexpected late snowmelt threatened to destroy Glen Canyon Dam.

For almost 100 years, scientists, water agencies and environmentalists have known that the status quo on the Colorado River is not sustainable. Over the last two decades, population growth and especially low runoff have exacerbated an already untenable situation.

The dire conditions and impending changes in the Colorado basin are all over the news. The U.S. government and the many water agencies involved are negotiating future management decisions. Everyone will be doing some serious belt-tightening; some more so than others.

How did we get here?

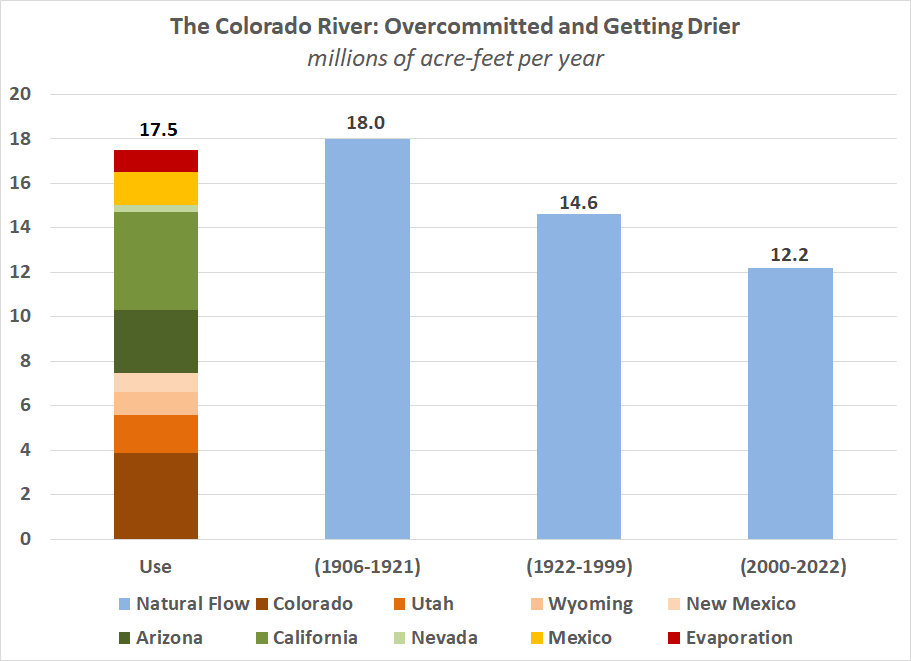

The Colorado River Compact (aka the Law of the River) was signed in 1922 after an uncommonly wet 16-year period, when the river’s average annual flow measured 18.0 million acre-feet (18.0 MAF). (A single family home might use 1/2 an acre-foot per year).

The Compact’s hallowed text apportioned 15 MAF of river flow among 7 southwestern states (see below). An additional 1.5 MAF per year would be be provided to Mexico. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation built huge storage reservoirs, including Lake Mead (holding up to 29 MAF behind Hoover Dam) in 1936 and Lake Powell (holding up to 24 MAF behind Glen Canyon Dam) in 1963, which together lose about 1 MAF to evaporation. So the total use of the Colorado’s flow plus expected evaporation would be about 17.5 MAF

The Colorado has long been fully subscribed – it has been many decades since its flows reached the Gulf of California.

Between 1922 and 1999, however, Colorado River flows averaged only 14.6 MAF. Oops.

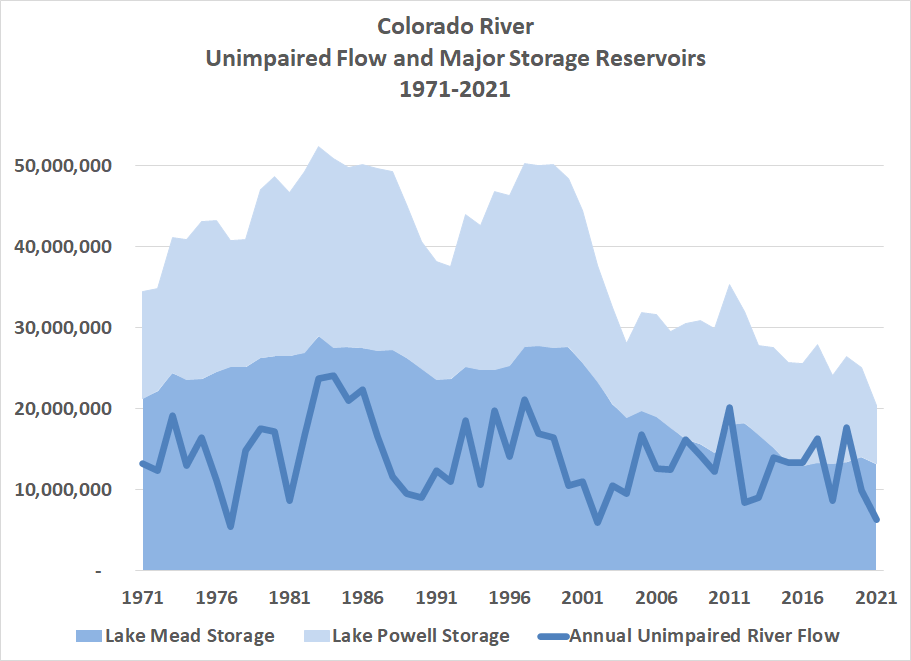

It’s surprising that the current crisis did not occur sooner. But some of the States were not using their full entitlements during the mid 20th century. And, as diversions increased at the end of the 20th century, there were a series of very wet years in the early 1980’s and late 1990’s (in 1983, high water threatened Glen Canyon dam – see the Bureau’s video or better yet read “The Emerald Mile”).

In the 21st century, however, there have been few high water years. In fact, the river’s flow has dropped further – to only 12.2 MAF. The system has been relying on withdrawing water stored in Lakes Powell and Mead. In 1999, these two mega-reservoirs held close to 50 MAF; today they are down to 20 MAF – a decrease of 60%

Whether the recent decline is the natural hydrologic cycle or has been caused by climate change is open to debate. What is not debatable is that cities and farms that depend on the Colorado must make major adjustments.

We are all concerned about water in the west. The situation at Hetch Hetchy is very different in that the Tuolumne River is a stream that feeds the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta – a system that depends on water going out to sea, not only to sustain the environment but also to allow transport of water within California from the wetter north to cities and farms in the south.

Restore Hetch Hetchy does not take a position on how divide Tuolumne River’s water between diversions to the Bay Area, supply for farms in Turlock and Modesto and downstream flow to the Delta. We are committed, however, to replacing the storage that the O’Shaughnessy Dam provides so Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National park can be restored to its natural splendor.