by Spreck | May 20, 2022 | Uncategorized

Restore Hetch Hetchy’s Spring 2022 Newsletter is available online. If you’d like a hard copy and have not received one, send your name and address to admin@hetchhetchy.org.

Included are:

- An update of our Keeping Promises campaign, discussions with the Park Service about extending access at Hetch Hetchy and building a short new trail to the top of Tueeulala and Wapama Falls;

- The premiere of Finding Hetch Hetchy, starring world-class climbers Timmy O’Neill and Lucho Rivera – available online soon;

- How restoring Hetch Hetchy differs from the Bay-Delta Plan when it comes to delivering water to California’s water cities and farms;

- Restore Hetch Hetchy’s role in removing signage in Yosemite Valley that was inaccurate and offensive to Native Americans;

- Tiffany Rosso, our awesome new Director of Development;

- Our upcoming Annual Dinner, September 17 at the San Mateo County History Museum; and

- Why you should visit Hetch Hetchy this year.

by Spreck | May 13, 2022 | Uncategorized

Hetch Hetchy Reservoir not only drowns a valley, it cuts off access to the surrounding canyon.

We’ve said it a million times. Restore Hetch Hetchy understands water storage is essential and that we do need dams (as well as improved groundwater storage). We simply don’t believe an iconic glacier carved valley in Yosemite National Park is the the right place for a dam and reservoir – especially when there are alternatives for storing the water elsewhere.

Dams do provide benefits. In California and the semi-arid west, dams store water from winter rains and spring snowmelt for delivery to cities and farms in summer and fall, as well as for carryover supplies in case the following year is dry. Dams also make it possible to generate hydropower. And many dams (although not O’Shaughnessy Dam at Hetch Hetchy) are required to maintain space for flood control.

In most cases, dams and reservoirs are managed to provide public benefits beyond water supply, hydropower and flood control. These benefits include:

- Reservoir-based recreation – swimming, fishing, camping etc.

- Healthy fish populations – by releasing sufficient instream flows for spawning and rearing downstream – sometimes to mitigate for the loss of spawning habitat caused by their construction, and

- River-based recreation – by releasing flows in conjunction with opportunities for rafting, canoeing and kayaking.

Even given Congress’ unprecedented permission to build a dam in national park, with regard to these other public benefits – San Francisco has struck out.

Strike 1: As we have explained at length in Keeping Promises: Providing Public Access to Hetch Hetchy Valley, Yosemite National Park, San Francisco committed to provide substantial access to the Hetch Hetchy area if it would be allowed to dam the valley, The City then reneged on those promises. Today, a paucity of trails and the City’s refusal to consider a non-polluting electric tour boat prevent visitors to Yosemite from accessing the backcountry in their national park. (East Bay MUD, for example, provides rental canoes and allows camping at its Pardee Reservoir.)

Backpackers frolic in the hard-to-reach Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne (Photo: Outdoor Adventure Club)

Strike 2: San Francisco continues to resist providing additional flows to help downstream fisheries. Along with other water interests on the Tuolumne River, San Francisco has declined to sign even the Newsom Administration’s (compromise) voluntary agreement to provide modest flows and funds to improve spawning habitat. The agreement was signed by a multitude of water agencies, including the largest in the Central Valley and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. A plethora of prominent environmental and fishing groups is applying pressure on San Francisco to provide additional water for downstream fisheries.

Chinook salmon (Photo: National Park Service)

Strike 3: In the wake of California’s overabundance of solar power during sunny afternoons, San Francisco has abandoned its long-standing practice of releasing hydropower from Cherry Reservoir on a schedule to benefit whitewater rafting and kayaking on the very popular “Lumsden” stretch of the Tuolumne River. A few miles north on the American River, the Sacramento Municipal Utilities District is abiding by its agreement to provide recreational flows below Chili Bar Dam.

The Tuolumne is a wonderful whitewater experience. Photo: Whitewater Voyages

Our mission is to return the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park to its natural splendor ─ while continuing to meet the water and power needs of all communities that depend on the Tuolumne River. We can then return to the people Yosemite Valley’s lost twin, Hetch Hetchy – a majestic glacial-carved valley with towering cliffs and waterfalls, an untamed place where river and wildlife run free, a new kind of national park.

Even with the dam in place, however, San Francisco seems to be maximizing its own financial benefit at the expense of recreation and the environment – more so than other communities in California.

San Francisco needs to do better for the public on all fronts.

by Spreck | May 8, 2022 | Uncategorized

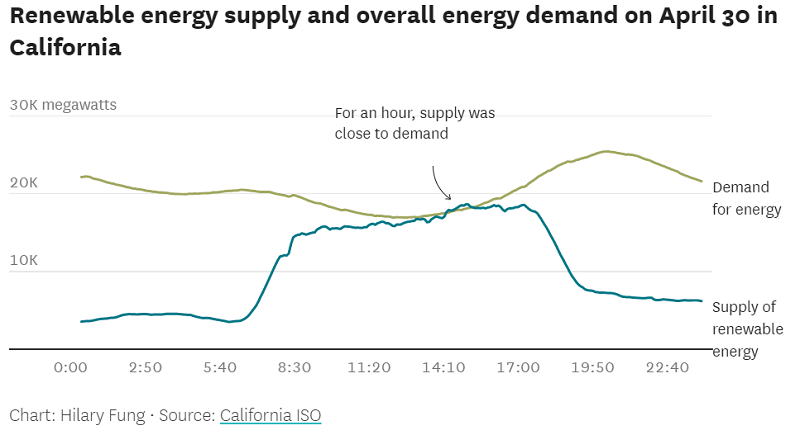

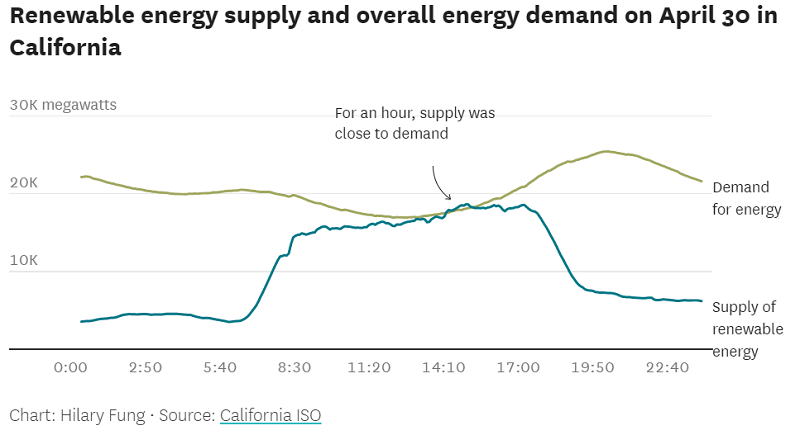

In the early afternoon of April 30, for the first time ever, California generated enough electricity from renewable sources to fully meet demand.

Hooray! But there is still a long way to go before meeting the State’s goals for 100% renewable power, or even getting close to that goal.

The achievement was realized on a windy and sunny afternoon in April. If it had been calm and overcast, or evening rather than afternoon, or August rather than April, renewable supply would have been far short of demand.

The growth in renewable power, especially solar and wind, continues. Improvements in energy storage are essential so power generated during daylight hours can be used at night.

And, while all technologies are imperfect, renewable power lessens impacts on the environment. Principally, the shift to wind and solar is intended to reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

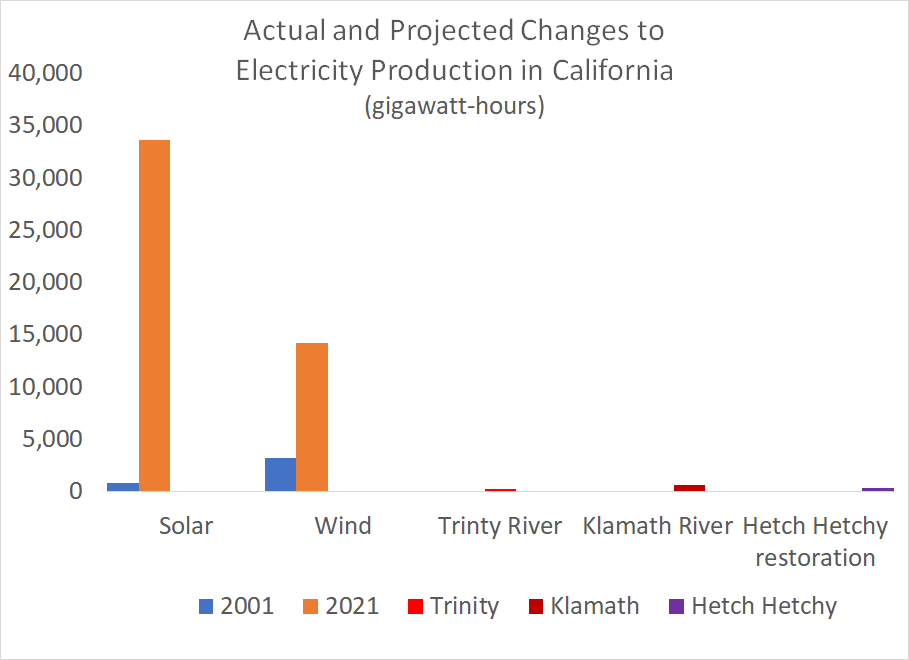

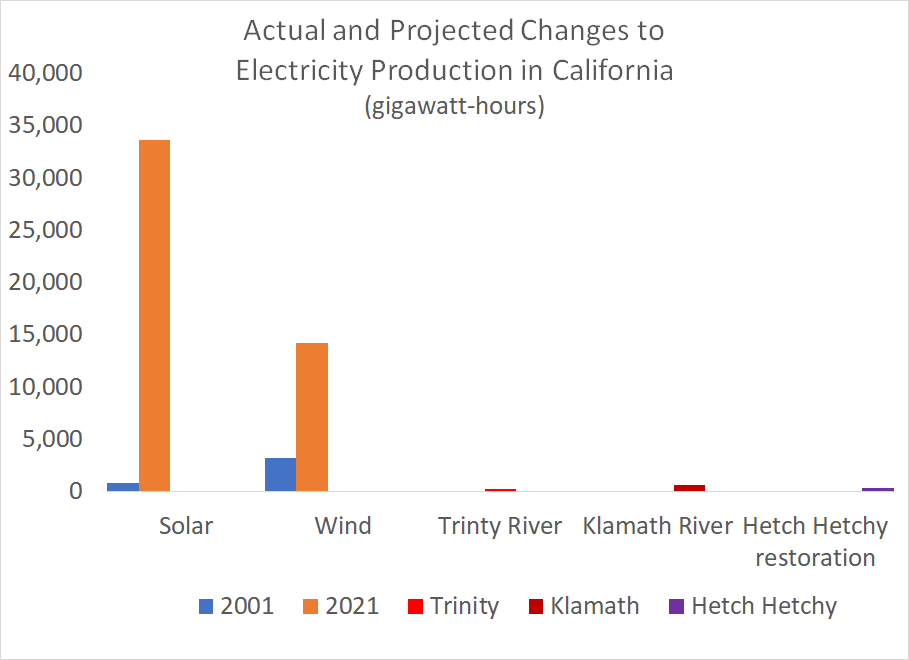

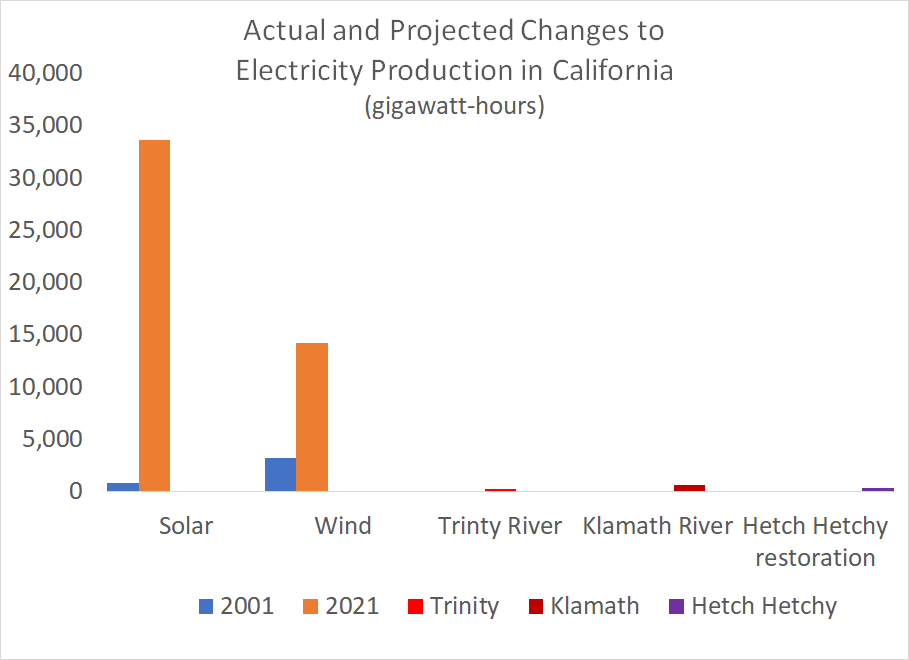

There are river restoration projects, however, which will result in relatively small losses of hydropower, including the Trinity (2000), Klamath (very soon?) and the Tuolumne through Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park.

by Spreck | Apr 30, 2022 | Uncategorized

2022 marks a third consecutive dry year in California. Urban water agencies in both southern California and the East Bay are mandating limits for their customers. And Central Valley farmers are making difficult decisions about what crops to grow and what fields to fallow.

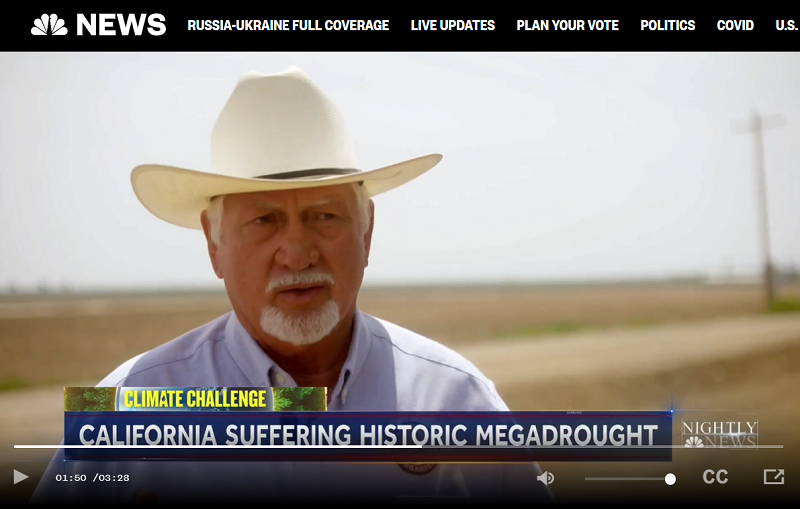

Joe Del Bosque grows organic melons in the San Joaquin Valley.

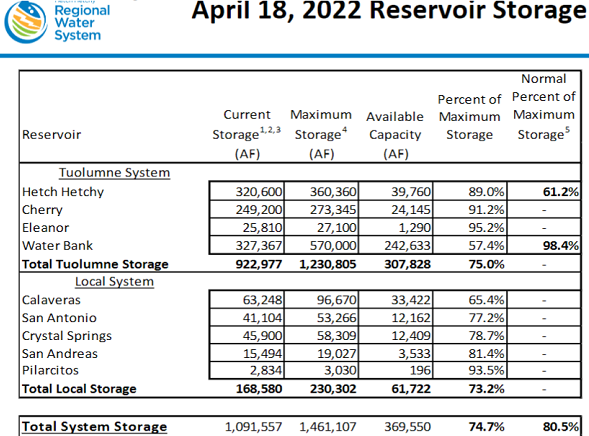

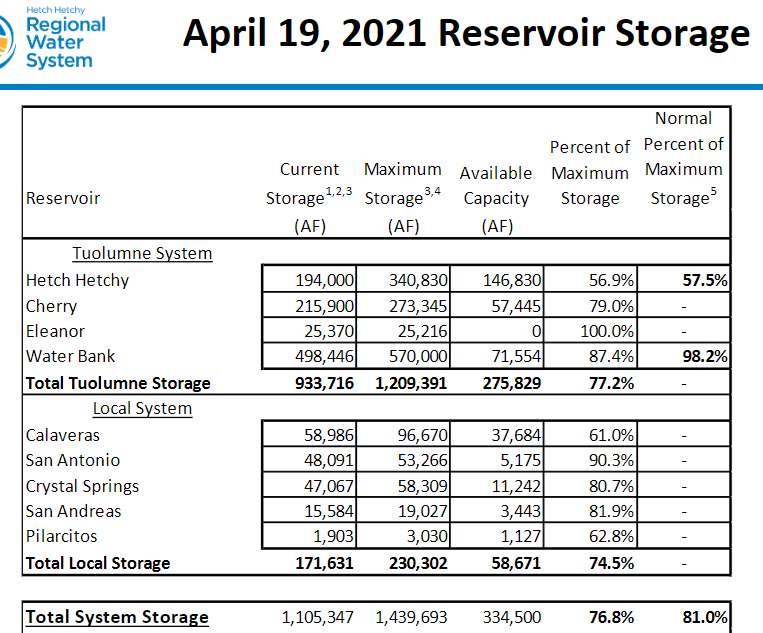

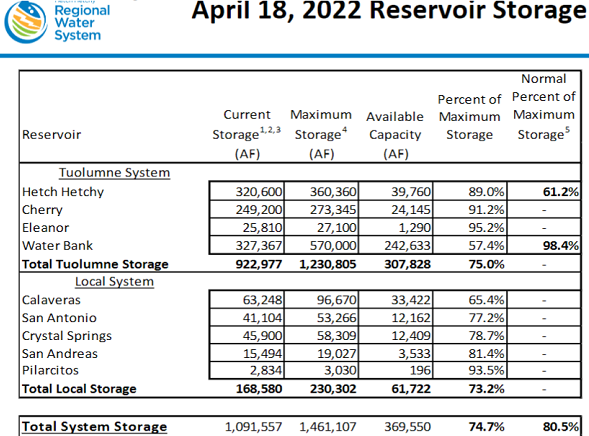

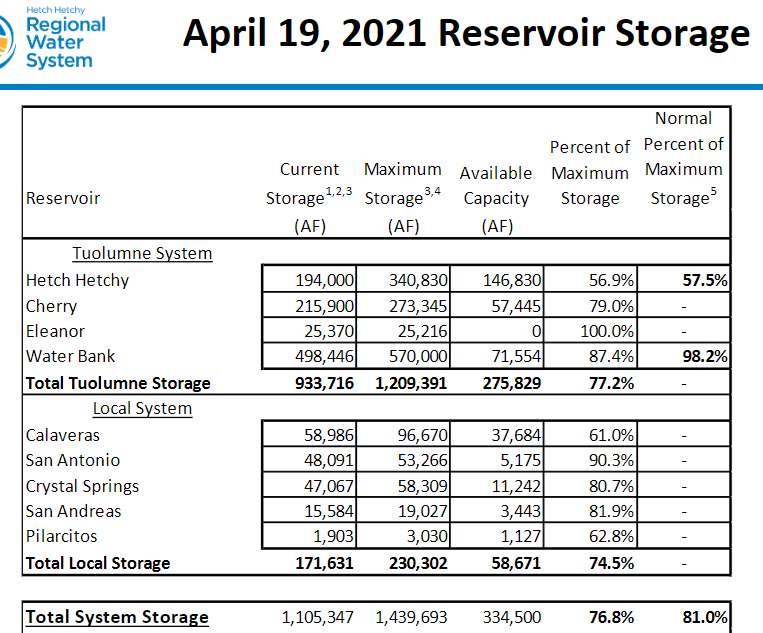

San Francisco, however, has relatively plentiful supplies in storage. Their nine surface reservoirs contain almost the identical amount of water that they did a year ago – more than a million acre-feet and roughly 5 years of supply. (San Francisco also operates two smallish groundwater banks.)

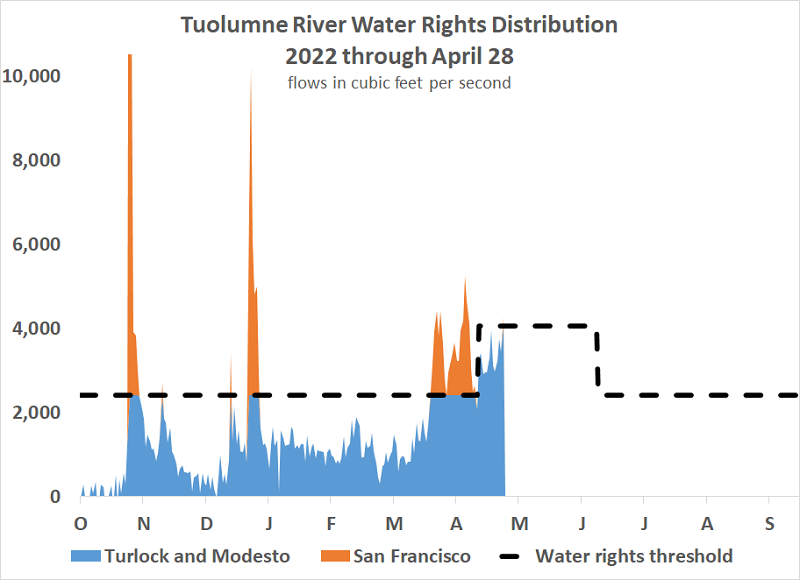

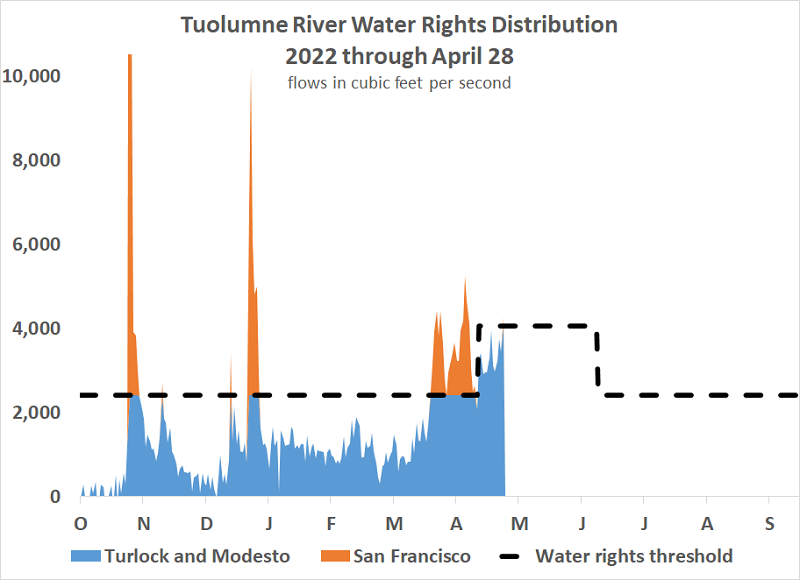

In some dry years, San Francisco’s junior water rights on the Tuolumne River yield almost no supply – the Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts get it all. 2022 was different. San Francisco received substantial amounts during the two early season storms that caused high flows on the Tuolumne River for short durations. Had that same amount of water flowed at lower rates for a longer period, none of it would have belonged to San Francisco.

(Water rights on the Tuolumne work like this: Natural flow is measured/calculated on a daily basis in cubic feet per second. For most of the year, the Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts get the first 2416 CFS, and San Francisco gets only those flows above that threshold. During the peak snowmelt season from mid-April through mid-June, that threshold increases to 4066 CFS. See below.)

Water rights on the Tuolumne and elsewhere in California can be described as inane and cattywampus.

While water agencies, including San Francisco, do need to operate conservatively to meet the needs of their customers, some argue that San Francisco hoards too much water in dry years.

Whatever level of reliability is warranted, Restore Hetch Hetchy urges San Francisco to invest in system improvements that will replace the storage function of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and allow Hetch Hetchy Valley to be restored.

by Spreck | Apr 22, 2022 | Uncategorized

Restore Hetch Hetchy has deep historical roots and an inspiring vision for the future.

Restore Hetch Hetchy has deep historical roots and an inspiring vision for the future.

We promote restoring Hetch Hetchy, Yosemite Valley’s lost twin, to its natural splendor; a majestic glacial carved valley with towering cliffs and waterfalls where river and wildlife run free. Hetch Hetchy can be a new kind of national park, with limited development, an improved visitor experience, shared stewardship with Native peoples, and permanent protection of its natural and cultural heritage for future generations.

We recognize the history of Hetch Hetchy’s destruction, as we build our campaign to realize this vision. twenty years ago, historian Robert Righter said it well when he titled his seminal book “The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: America’s Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism.”

Now we have yet another outstanding book. The University of Exeter’s Laura Smith has just published a compelling, thoroughly researched, treatise on five pivotal writers in American conservation. Ecological Restoration and the U.S. Nature and Environmental Writing Tradition: A Rewilding of American Letters weaves the writings of Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, and Edward Abbey into a common thread. Walden Pond, Hetch Hetchy, Leopold’s sand farm, the Everglades and Glen Canyon are different pieces indeed but all bring us closer to the magic of our natural world. Do yourself and Earth Day favor and get yourself a copy.

And many thanks to the author for sharing our inspiration to restore Hetch Hetchy and turn it into a new kind of national park.