by Spreck | Dec 10, 2022 | Uncategorized

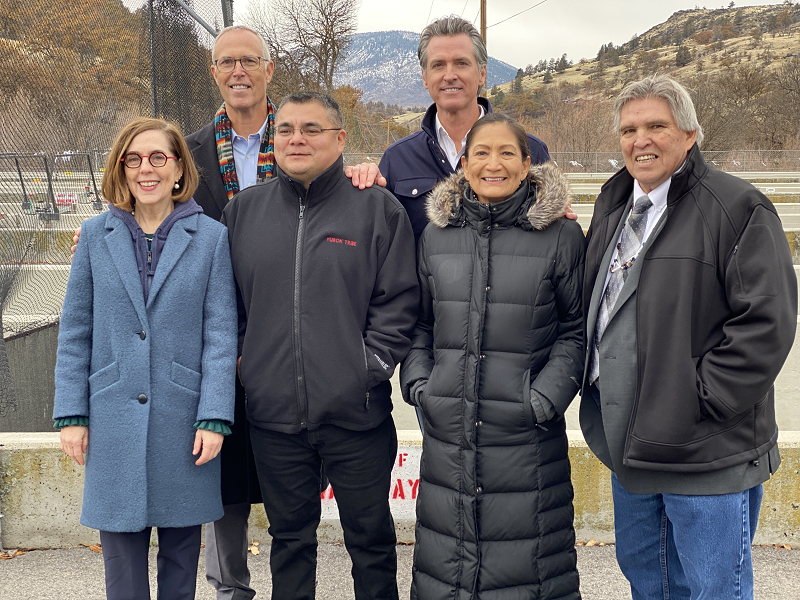

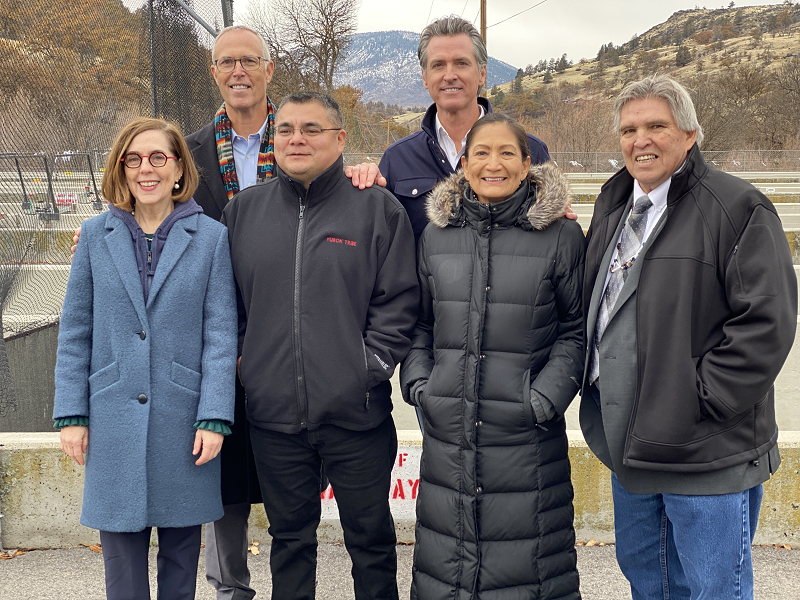

We’re happy to see Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Governors Gavin Newsom of California and Kate Brown of Oregon, and Congressman Jared Huffman celebrating the prospective removal of dams on the Klamath River with leaders of the Karok and Yurok Tribes. There is widespread agreement that the benefits of dam removal on the Klamath outweigh the hydropower benefits that the four dams provide.

From left, Oregon Governor Kate Brown, Congressman Jared Huffman, Yurok Tribal Chairman Joseph James, California Governor Gavin Newsom, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Karok Tribal Chairman Russell “Buster” Attebery

We’d like to ask Haaland, Newsom and Huffman to take a hard look at the opportunity to restore Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley. There is no better time than now.

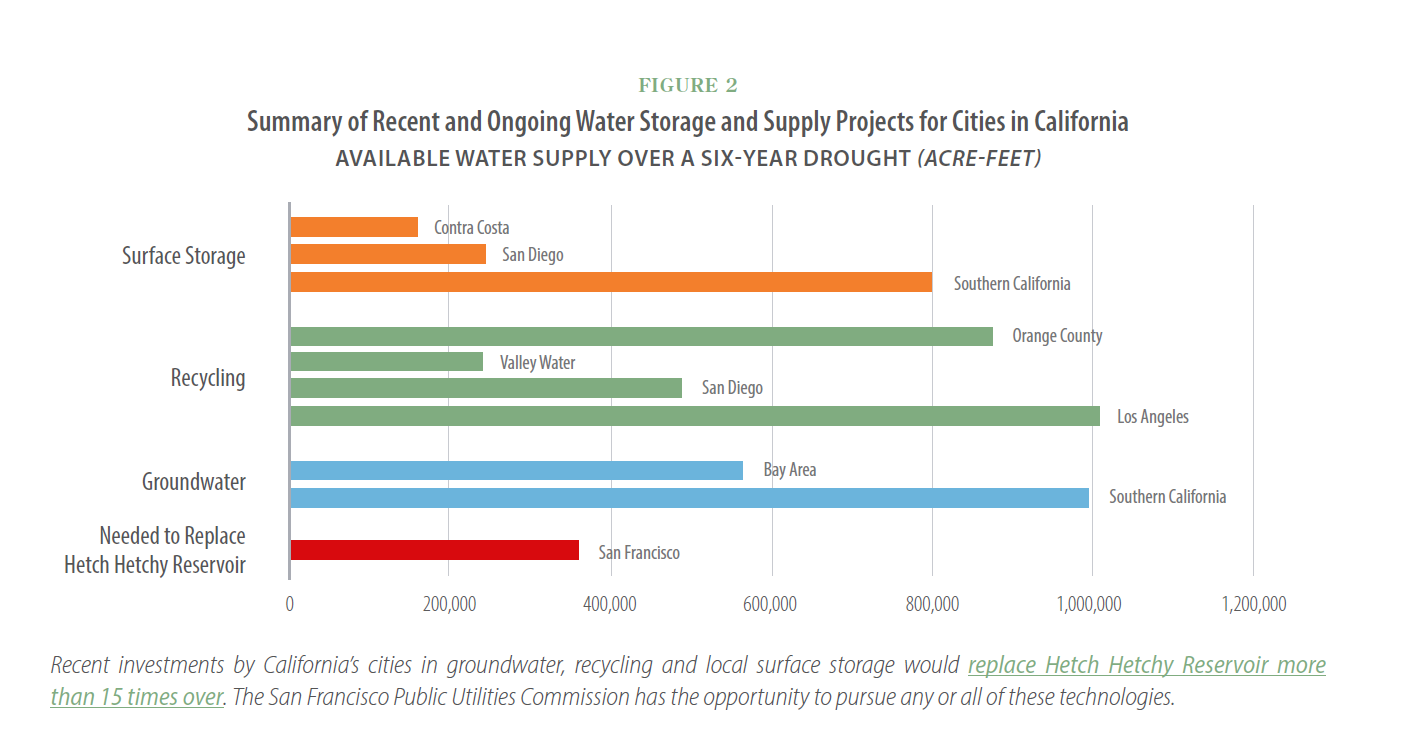

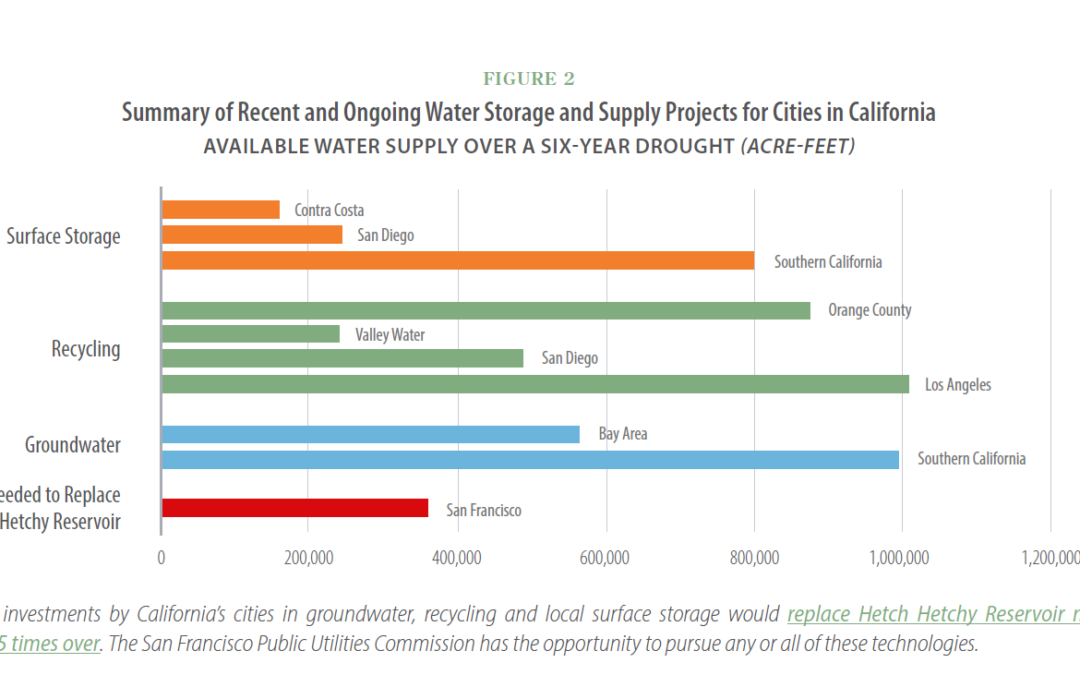

As we’ve made clear, Restore Hetch Hetchy is not anti-dam. In some cases, however, including the Klamath and Hetch Hetchy, the benefits of restoration clearly outweigh the benefits provided by the dams. Principally, dam removal on the Klamath will require annual replacement of 696 gigawatt hours of electricity by other means. That’s about twice the amount of power lost when Hetch Hetchy will be restored. Of course Hetch Hetchy will require replacement for lost water storage as well (as we recently showed in Yosemite’s Opportunity, other California water agencies are replacing at least 15 times what will be needed to keep San Francisco whole).

We’ve talked about restoration with both Newsom and Huffman, but not with Haaland. It’s fair to say that Newsom and Huffman understand that restoration is doable but have yet to see political advantage in supporting restoration. Newsom is an ex-Mayor of San Francisco but has shown unexpected leadership in the past in certain areas – will he do so on Hetch Hetchy? And Huffman is an ex-environmental attorney (NRDC) who worked hard on Central Valley fishery issues – how much does he care about Yosemite?

And what might it take for Secretary Haaland to take an interest in restoration as previous Secretaries of the Interior have?

The words of both Mahatma Gandhi (“When the people lead, the leaders will follow.”) and David Brower (“Politicians are like weather vanes. Our job is to make the wind blow.”) ring in our ears.

We all need to lead and to make the winds of change blow harder. We need to make our officials, Newsom, Haaland, Huffman and others, realize the tremendous opportunity and legacy that lies before them.

Before entering politics, Mahatma Gandhi was a lawyer.

by Spreck | Nov 25, 2022 | Uncategorized

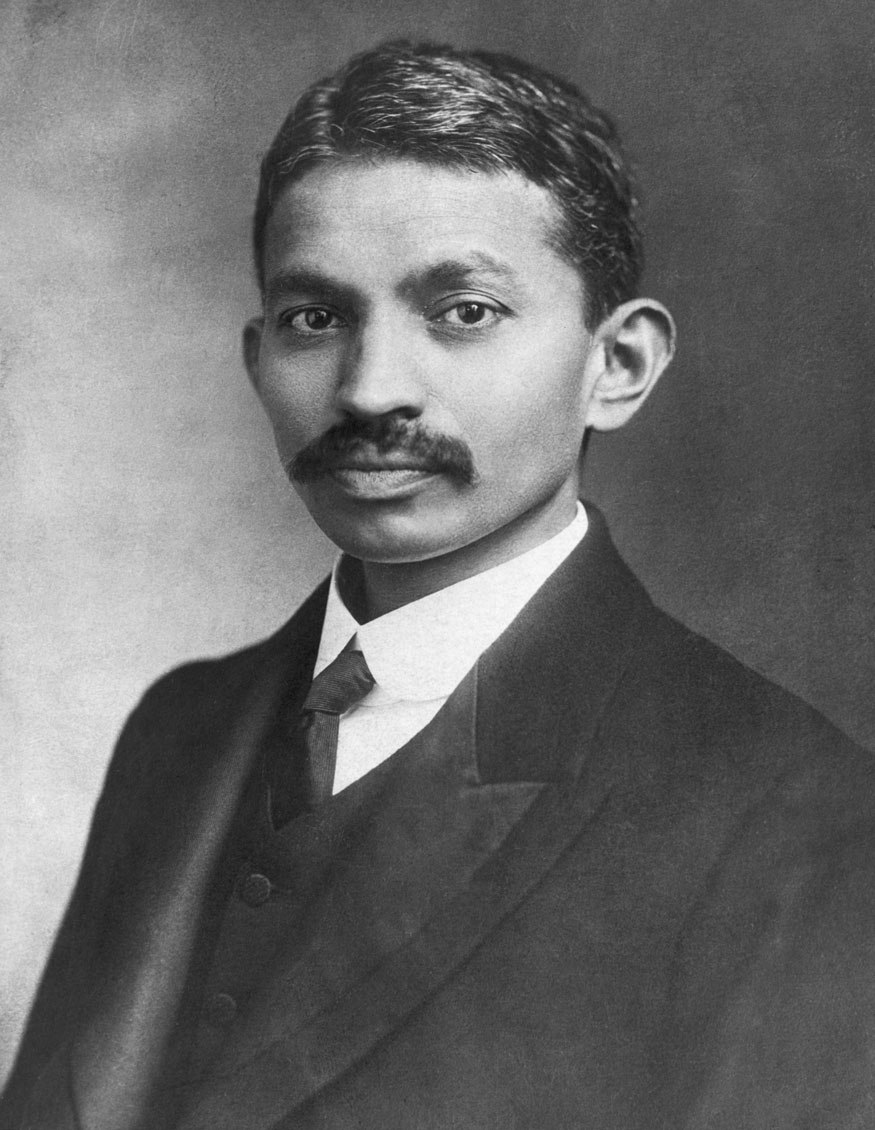

Yosemite’s Opportunity: Options for Replacing Hetch Hetchy Reservoir

Our latest report, Yosemite’s Opportunity: Options for Replacing Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, has been distributed by mail and is available online. If you haven’t received a hard copy and would like one, let us know.

Accomplishing restoration is dependent on keeping San Francisco whole with respect to water supply. It’s where the rubber hits the road. Fortunately, it’s doable – very doable.

Yosemite’s Opportunity is shorter in length than previous reports by Restore Hetch Hetchy, Environmental Defense Fund, UC Davis and the Bureau of Reclamation. It has a slightly different focus in that it shows what other water agencies have been doing for decades and that the same options are available to San Francisco.

Two of the options highlighted by Yosemite’s Opportunity – recycling and groundwater banking, are more attractive than ever. Recycling not only increases water supply, it also reduces the pollution from water treatment plants that harms our rivers, bays and beaches. Banking groundwater in Turlock, Modesto and Eastside would not only benefit San Francisco but would help those areas cope with their own groundwater overdraft problems.

We have already distributed Yosemite’s Opportunity to officials in San Francisco, water agency leaders throughout California, interested journalists and many others. We will be sending the report to elected officials in Washington D.C. and Sacramento in January as new legislative sessions begin, and we plan to follow up with committee leaders and other selected members. We are pleased that members have taken interest in our Keeping Promises Report – and introduced legislation. We hope they will do the same with Yosemite’s Opportunity.

———————–

We are pleased that Vimeo has highlighted Finding Hetchy Hetchy as a “Staff Pick” and that it is racking up views by the thousands. Watch it there or on our website.

by Spreck | Nov 18, 2022 | Uncategorized

FINDING HETCH HETCHY: The Hidden Yosemite, a film highlighting the extraordinary rock climbing opportunities at Hetch Hetchy is now available for viewing online. Have a look and let us know what you think. And please share it with your friends.

Timmy O’Neill and Lucho Rivera climb the rarely-visited walls of Hetch Hetchy Valley, famously compared by naturalist John Muir to Yosemite Valley itself.

Finding Hetch Hetchy tells the story of Timmy O’Neill’s first trip to Hetch Hetchy. Timmy has spent three decades scaling the monoliths in Yosemite Valley (and is currently Executive Director of the Yosemite Climbing Association) but, like so many climbers in the park, had never visited Hetch Hetchy. He is guided by Lucho Rivera who, along with his wife Mecia Serafino, is one of the few climbers familiar with Hetch Hetchy’s granite walls. Shortly after the filming, Lucho and Mecia joined the board of Restore Hetch Hetchy.

Joining Timmy and Lucho on Hetch Hetchy Dome were filmmaker James ‘Q’ Martin and his crew, cinematographer Mikey Schaefer and sound man/rigger Nelson Klein. Burkard Studios put the team together and Chris Burkard also supplied rarely seen footage of the top of Wapama Falls.

Rock climbing is not for everybody; but it’s something we can all appreciate. The walls at Hetch Hetchy provide wonderful opportunities for climbers willing to go a bit further and work with the National Park Service’s limitations to access the area.

Restore Hetch Hetchy wants to improve access for all visitors to Yosemite – families, hikers, birdwatchers, fishermen as well as rock climbers – everyone. There’s lots to see and appreciate – even with the dam in place. Importantly, we are confident that people who visit Hetch Hetchy, see its beauty and learn its story will support relocating the existing reservoir and returning Hetch Hetchy Valley to its natural splendor.

“What is really unique about climbing in Hetch Hetchy is how few people are there. It is truly this wild place. You always hear Hetch Hetchy is equal in beauty to Yosemite Valley. That is true, “ says O’Neill in the documentary. Of the mission to restore the Hetch Hetchy Valley, O’Neill says: “I see the ability to have a clean slate, a blank canvas, where you take the lessons learned from Yosemite Valley but have it be cleaner, quieter and less congested.”

When Congress created Yosemite National Park in 1890, Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy, once home to Native Americans, was to be protected in perpetuity. In the early 1900s, however, San Francisco launched a campaign to dam and flood Hetch Hetchy and won Congressional approval, in 1913, to do so, burying the extraordinary valley under water and making the surrounding canyon nearly inaccessible to visitors. Although the unprecedented battle to stop the dam was unsuccessful, it helped launch the international environmental movement.

“Yosemite Valley is well-known as the epicenter of American climbing, but Hetch Hetchy, its sister valley to the north, has long been left in its shadows, despite being part of Yosemite National Park. When Hetch Hetchy is restored to its natural splendor, it will be another mecca for climbers—as well as for those who simply like to watch them from terra firma,” said Martin who co-directed the film. “It was thrilling to shoot on those towering granite walls as Timmy and Lucho took on this climbing challenge, and an honor to be part of bringing a message of both access and restoration, to climbers and the outdoor community, about this remarkable place.”

Restore Hetch Hetchy staff and volunteers joined the climbing team and film crew for a hearty dinner at the Evergreen Lodge the evening before the three day ascent of Hetch Hetchy’s granite cliffs. Clockwise from lower left, Erika Ghose, Evan Ruderman, Jeff Brundage, Chris Burkard, Mikey Shaefer, Timmy O’Neill, Mecia Sarafina, Julene Freitas, Virginia Johannessen, Spreck Rosekrans, Lucho Rivera, James Q Martin, Nelson Klein and Jack Pier.

We are proud to have worked with these extraordinary filmmakers and climbers to help raise awareness of our mission to relocate the reservoir outside Yosemite and restore Hetch Hetchy Valley to its natural splendor. Our vision is to return this glorious place to the people as a new kind of national park, with shared stewardship, an improved visitor experience and protection of its natural and cultural heritage. We believe restoration will be an inspiration to people across the globe.

by Spreck | Nov 11, 2022 | Uncategorized

Hetchy Hetchy’s role in American history is best known to many of us by the political battle, culminating in the 1913 passage of the Raker Act, which pitted San Francisco against John Muir and the nascent Sierra Club. Hetch Hetchy’s human history did not begin, however, with Muir’s many trips to Hetch Hetchy in the 1870s, nor even with the Screech Brothers who first visited in 1850.

Hetch Hetchy is the ancient homeland of nearly a dozen Indigenous peoples, including Sierra Miwok, Yokuts, Washoe, Western Mono, and Paiute. The word Hetch Hetchy may refer to the name of a Miwok village in the valley and/or to “a kind of grass or plant with edible seeds abounding in the valley.” Alternatively, the valley is referred to as Iyaydzi in the Paiute language. Regardless of the name used, for thousands of years indigenous people were the stewards of this special place – hunting, burning, pruning, cultivating, seeding, transplanting, utilizing and caring for important plant species. (For more information see Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources, M. Kat Anderson, 2013)

Accordingly, RHH strongly supports Tribes in having a meaningful and active participation in the restoration, management and use of Hetch Hetchy. In this spirit, we are sharing the memorandum sent to NPS staff from Director Chuck Sams, its first Native American Director, in celebrating Native American Heritage Month:

Chuck Sams, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, served in the United States Navy from 1988 to 1992.

From: Director, NPS <NPS_Director@nps.gov>

Sent: Wednesday, November 2, 2022 12:42 PM

Subject: Celebrating Native American Heritage Month

Dear Colleagues,

I’m deeply proud to join you for the first time as Director in celebrating Native American Heritage Month. It’s an immense honor to lead the National Park Service as we work to strengthen Indigenous connections and enhance our nation-to-nation relationships with Tribes. I’m moved by the significance of being the first American Indian to hold this office, but I’m also often reminded by my elders that, regardless of what title I hold, I have a responsibility to steward natural resources not just for myself, but for the generations to come.

This is a time for us to uplift the traditions, languages, and stories of Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and to ensure their rich histories and contributions continue to thrive with each passing generation.

Recently, I had a chat with Drew Lister, an intern in our Office of Native American Affairs and member of the Council for Indigenous Relevancy, Communication, Leadership and Excellence (CIRCLE). We shared thoughts about our lived experiences as Native Americans working for the National Park Service, and I invite you all to watch the video.

I want to thank CIRCLE for supporting our employees and sharing recommendations on hiring, retention, and improved visibility of Native Americans throughout the NPS.

While there is always work to be done, I’m grateful for the progress we’re making on key issues. Following extensive Tribal consultation, the Department of the Interior is proposing changes to Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act regulations to streamline the process for returning human remains and sacred and cultural objects to Indigenous people. The Department has also issued new guidance to strengthen Tribal co-stewardship of public lands and waters. NPS employees can learn more about co-stewardship in upcoming webinars from the Office of Native American Affairs on November 17, December 7, and January 13.

Employees can also participate by observing Red Shawl Day on November 19, a time to bring attention to violence committed against Native Americans, particularly women and children. According to the Department of Justice, Native American and Alaska Native women go missing and are murdered at a rate more than 10 times higher than the national average. All NPS employees and volunteers, including uniformed employees, are invited to join the observance, on November 19, 2022.

I also invite Indigenous employees, volunteers and visitors to join in Rock Your Mocs week, November 13-19. It’s an opportunity to celebrate Tribal individuality, honor our ancestors and Indigenous people nationwide by wearing traditional footwear.

Thank you all for your support, and your dedication to our mission, and for the commitment to stewardship that we share with Native Americans.

Chuck

Charles F. Sams III

Director, National Park Service

by Spreck | Nov 5, 2022 | Uncategorized

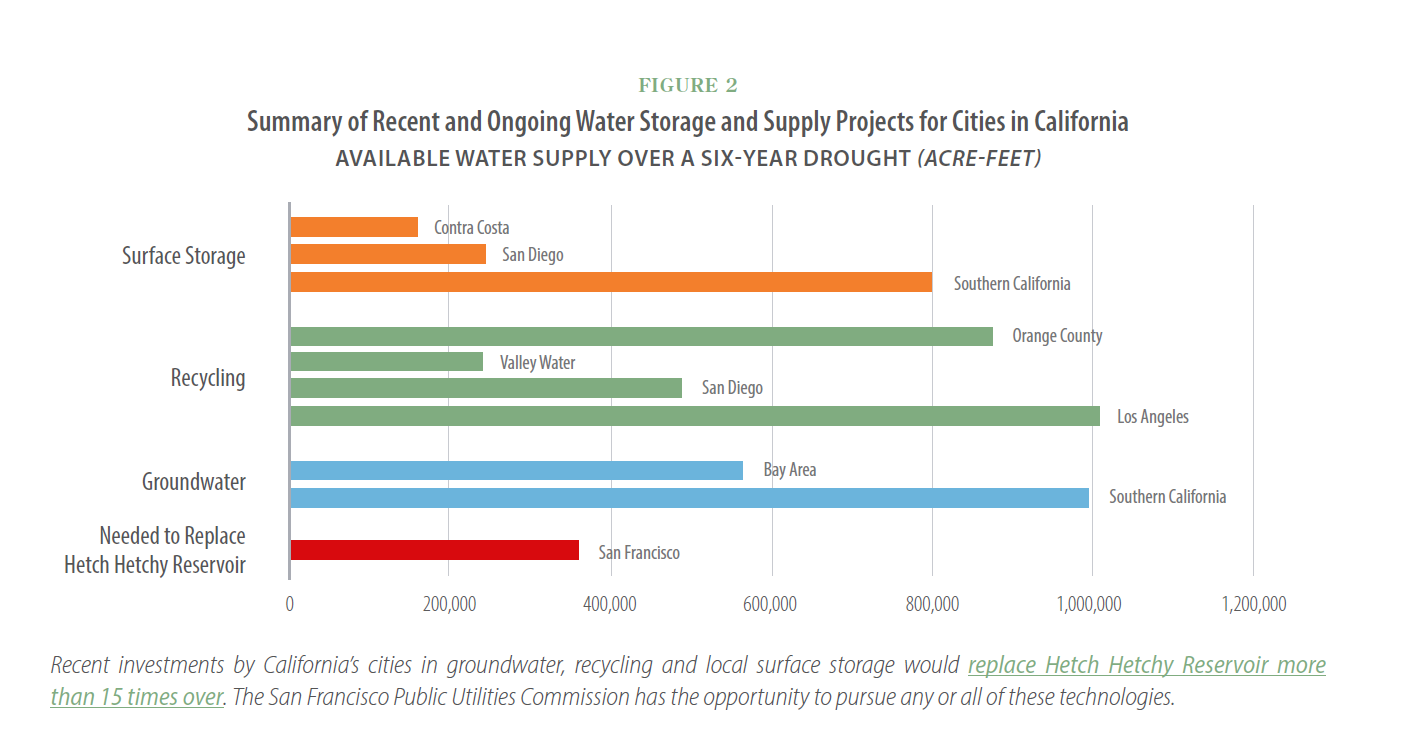

Representative Connie Conway has introduced a bill in the House of Representatives to increase visitor access and recreation in the Hetch Hetchy area of Yosemite Park and to increase San Francisco’s “rent” for use of the national park. The Yosemite National Park Equal Access and Fairness Act (a quick read, check it out) is cosponsored by Representatives David Valadao and Tom McClintock. See the Valley Voice for quotes from the sponsors.

Provisions of the bill would allow swimming, non-motorized watercraft, camping & picnicking at Hetch Hetchy and Lake Eleanor. (Restore Hetch Hetchy has been advocating for these improvements, except swimming which is banned by current law.)

Restore Hetch Hetchy has had no direct contact with the Congressional sponsors, but many of the recommendations from our Keeping Promises report are embodied in the bill.

The bill would also increase San Francisco’s “rent” immediately from $30,000 per year to $2,000,000 per year. A subsequent increase would be much greater as the proposal directs the Department of Interior to increase the rent by the value of foregone recreation had the valley never been flooded.

(In addition to $30,000 in rent, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission currently pays Yosemite National Park about $8,000,000 per year in watershed protection and security costs out of its $1,300,000,000 operating budget.)

While the proposed legislation reflects many of our priorities, Restore Hetch Hetchy has had no direct contact with the bill’s sponsors. We have, however, sent materials to all members of the House Interior Committee, including:

The Representatives may also have read The Dam Rent Is Too Low, a report published by the Property and Environmental Research Center, which recommends a substantial rent increase.

Restore Hetch Hetchy is pleased to see the proposed legislation. We hope a robust discussion of the merits will ensue and that we will be able to play a helpful and meaningful role in the months ahead.

Restore Hetch Hetchy is not naïve. We understand that this proposed legislation will be embroiled in a larger political debate. We will, as we always have, stay focused on the merits. Hetch Hetchy, Yosemite, and all our national parks, are too important to do otherwise.

Our vision – returning to the people Yosemite Valley’s lost twin, Hetch Hetchy – a majestic glacier-carved valley with towering cliffs and waterfalls, an untamed place where river and wildlife run free, a new kind of national park – remains the same. Increasing access and recreation is an important and necessary step toward restoration.

Take Action Now

If you have not already done so, please sign our letter to Yosemite Superintendent Cicely Muldoon asking the National Park Service to improve access at Hetch Hetchy.

by Spreck | Oct 30, 2022 | Uncategorized

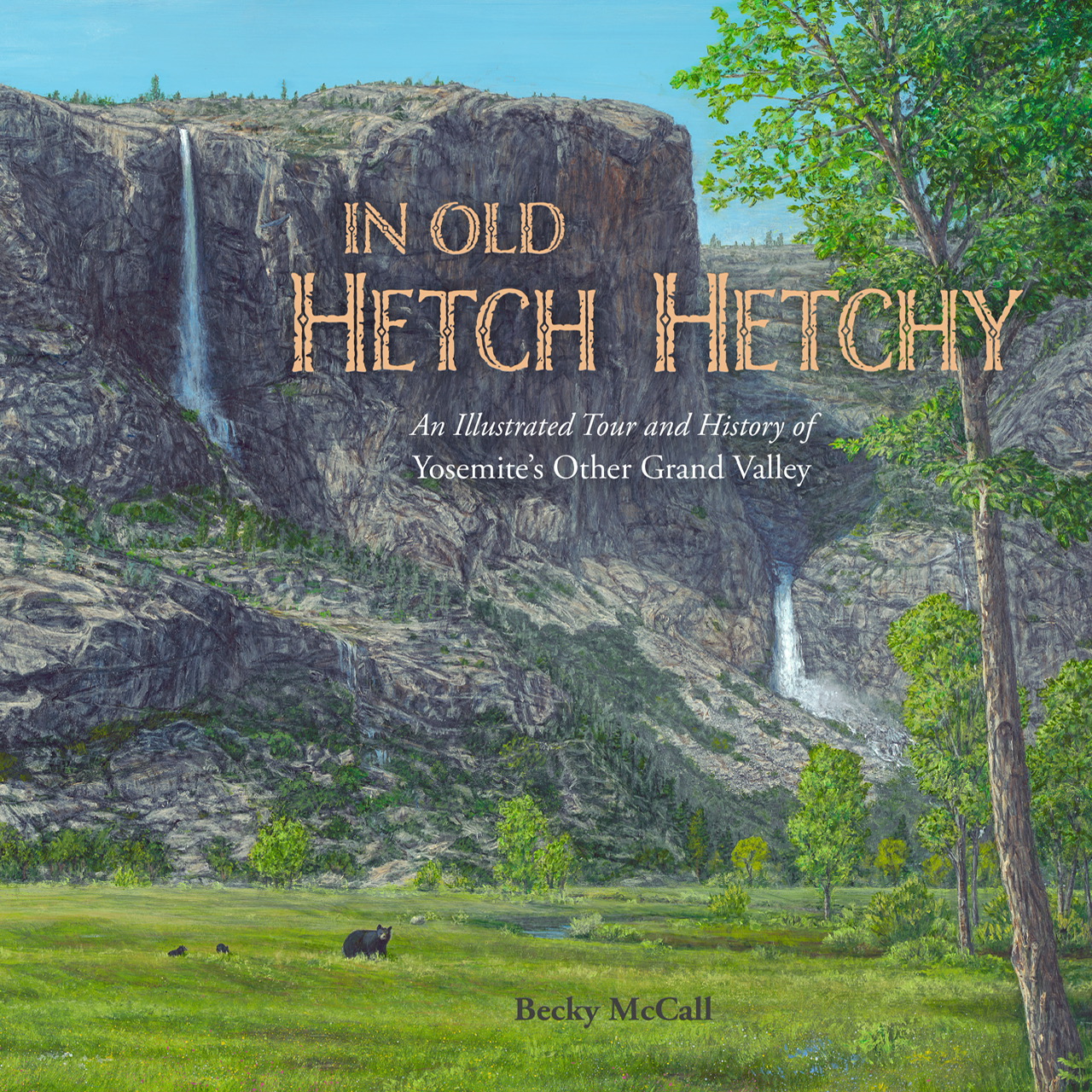

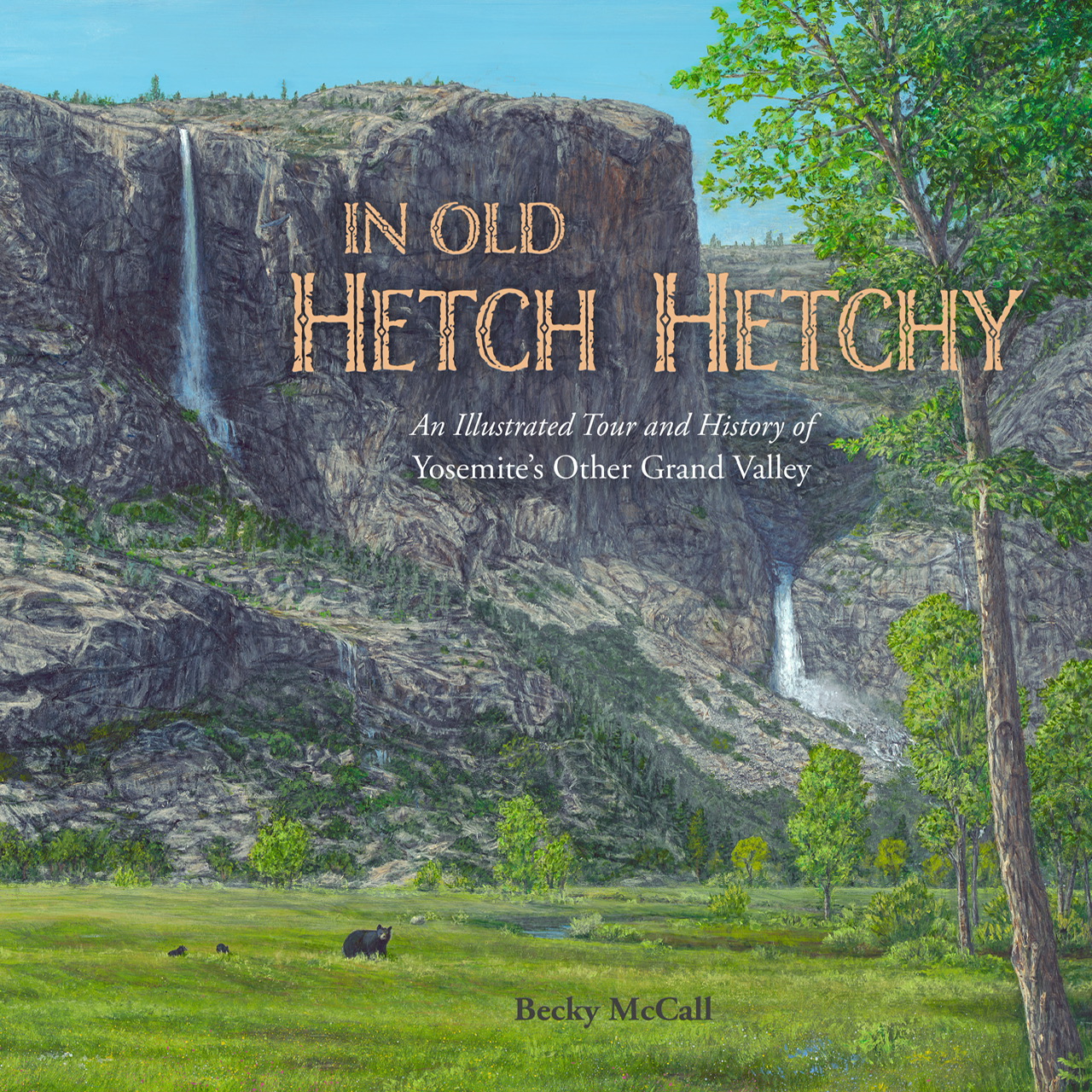

In Old Hetch Hetchy: An Illustrated Tour and History of Yosemite’s Other Grand Valley is a comprehensive and compelling book for anyone interested in the past, present or future of Hetch Hetchy.

Becky McCall visited Yosemite several times as a child, but never realized Hetch Hetchy existed until she stumbled onto an article in high school. In Old Hetch Hetchy is the product of years of impressive research.

McCall’s lush paintings provide backdrops to detailed descriptions of Hetch Hetchy’s many separate meadows, waterfalls, and rock formations, as well as its flora and fauna. They welcome the reader into the historic valley and stir the imagination. There is a lot to see and explore on page after page.

Turning to Hetch Hetchy’s human history, McCall’s research begins with the Indigenous peoples who used Hetch Hetchy before California’s gold rush brought an influx of Americans into the Sierra. Apangasse Chief Nomasu, and Enyeto, son of Aplache Chief Hoho, were born there. For a time in the 1850’s, after the Mariposa War, different bands of Native Americans found refuge in the more remote and lesser-known Hetch Hetchy Valley.

McCall recants tales of the Screech Brothers, who found Hetch Hetchy to be an ideal place for sheep grazing and blazed a crude road to the valley. John Muir visited four times in the 1870s and subsequently lobbied Congress to create Yosemite National Park, including Hetch Hetchy Valley. McCall also unearthed the story of four women, Berkeleyans Helen and Lulu Gompertz and San Franciscans Belle and Estelle Miller, who took a two-month “unchaperoned” camping trip to Hetch Hetchy in August 1895, tramping about the valley in their bloomers.

McCall is no fan of the Raker Act but provides an honest accounting of the politics as well as the engineering challenges of building the O’Shaughnessy Dam. She speaks to the City’s sudden change of attitude toward visitors once the Raker Act was passed, including conflicts with Stephen Mather, the National Park Service’s first Director.

McCall concedes that Hetch Hetchy Reservoir provides benefits to the Bay Area, as we do at Restore Hetch Hetchy, and is inspired by new ideas, including returning the valley to its natural splendor.

Buy the book. Or better yet, buy two copies – keep one and give one to a friend.